Music video: Down With The King by RUN DMC - stickers by Pulp Conversations

When most people think of venture capitalists (VCs), they imagine high-powered financiers, masters of the universe who pick winners and losers with the precision of Wall Street traders. But the reality is far more nuanced—and, in many ways, more interesting.

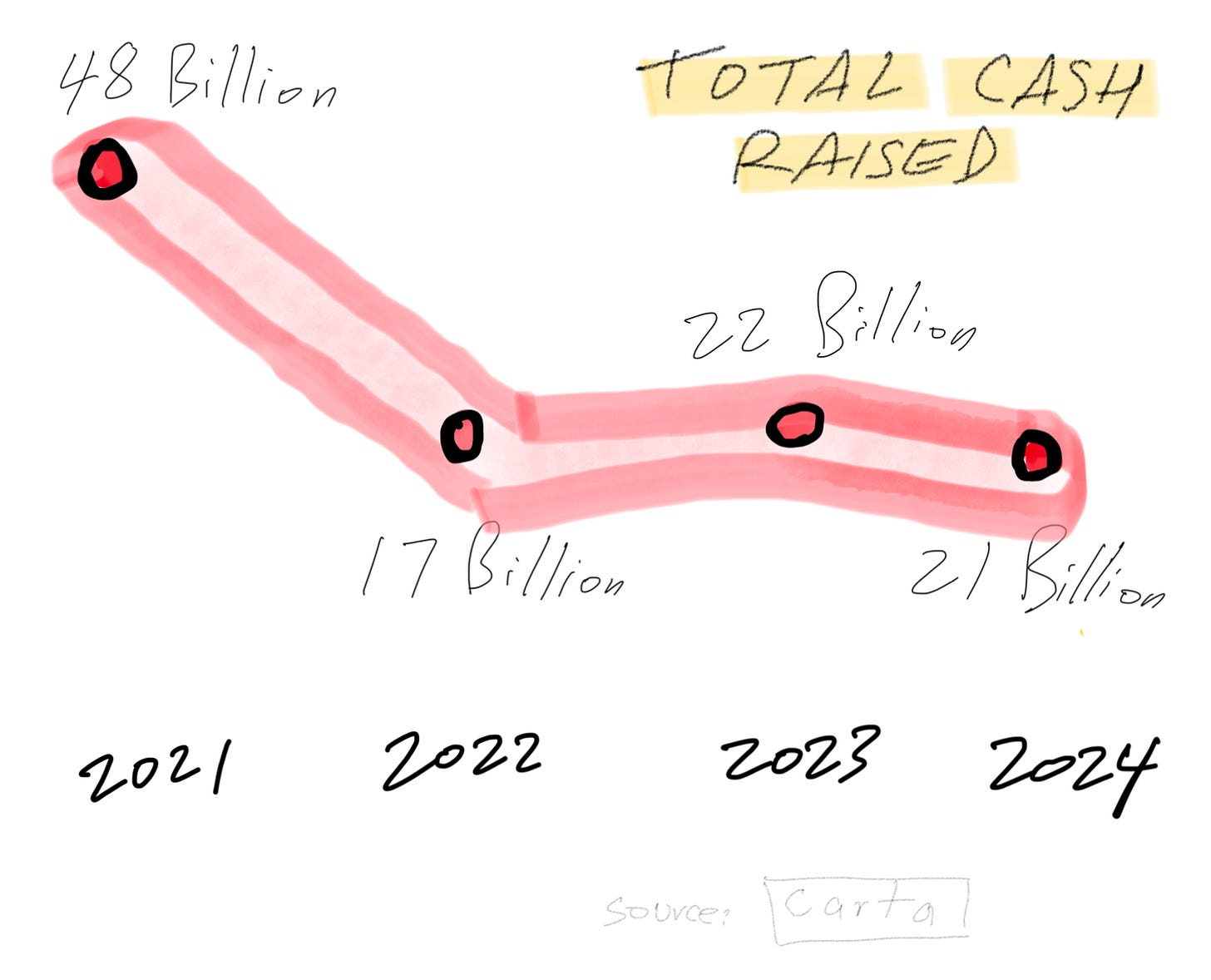

Not hockey stick growth 👆🏽.

Product-Market Fit: So Seductive yet elusive

Let’s start with the holy grail of startups: product-market fit.

Figuring out how to achieve it takes real skill. But actually achieving it? That’s where a healthy does of luck comes in.

Bad idea, bad timing = FAILING Good idea, bad timing = failing Good execution, bad timing = failing Ok execution, good timing = winning Good execution, great timing = WINNING

No matter how sharp a VC’s instincts are, the unpredictable nature of ideas, suppliers, founders, employees, macro markets and consumer behavior means that even the best can’t guarantee success.

A more accurate analogy for VCs might be the A&R (Artists and Repertoire) reps at a music label. Like A&R reps, VCs are constantly scouting for creative talent—founders with the potential to build something big.

Some VCs are true financiers, with the analytical chops to back it up. But many are not. In fact, most don’t have the je ne sais quoi to attract the “hottest artists founders in town.”

Caveat to the caveat: you don’t need super-analytical chops to be a VC.

The public perception of VCs as financial wizards is often misplaced.

At their core, VCs are market makers; figuratively and literally a poor men’s Jane Street.

They sit between limited partners (LPs)—the real source of capital—and founders, the entrepreneurs building the next big thing.

It’s the LPs’ money by-in-large that founders are spending, not the VCs’ own. The general partners (GPs) who run VC funds typically have only a small personal stake in the fund.

While that investment might be significant for them personally, it’s usually a drop in the bucket compared to the overall fund size.

Skin in the game.

This brings us to a crucial point: founders should always ask how much “skin in the game” their GP has. If the GP’s own money is only a tiny fraction of the fund, their incentives may not be fully aligned with the founders they back.

This lack of personal risk is what enables the classic “spray and pray” approach—investing in as many high-potential startups as possible, hoping that a few will hit it big and make up for the rest.

The Real VC.

The VC asset class is built on access to deals and the ability to place many bets. It’s less about carefully nurturing each investment and more about maximizing the odds that one or two will become runaway successes. This model works, but it’s important to understand what’s really going on behind the scenes.

Rethinking the VC Myth

Next time you hear about a VC “kingmaker,” remember: they’re often more like talent scouts than financial engineers.

Their real value lies in spotting potential and making connections—not in guaranteeing success. And for founders, the key is to look beyond the hype and understand who’s really taking the risk—and who’s just along for the ride.

Post Script

👑👑👑👑👑👑👑👑👑. 👆🏽

VC as an asset class is in a flux circa Spring 2025 in great part because it becomes less compelling to speculate on Hail-Mary-passes clocking a median IRR of 8 - 10% when the settlement-money of the future: FedWire Bitcoin itself is monetizing at a 66% CAGR since the start of 2019 (to May ‘25).