The Parisian "Piqueurs"

Pricks gonna prick ...

The Parisian "Piqueurs"

This is a translation from the page above that comes from:

A red book about fait divers from the 19th century - one of the pages is about that - so it’s a thing thats happened in the past.

Something only my talented sis-in-law could pattern-recognize, leaving my other talented sis-in-law to track down.

A new kind of epidemic struck Paris during the winter of 1818: men were pricking womenʼs backsides in the streets, in theaters, and in the galleries of the Palais-Royal.

The first “piqueur” was a man dressed as a half-pay officer, wearing the ribbon of the Legion of Honor. His victim, sitting on a bench in the Tuileries garden, suddenly felt a sharp pain in her lower back and lost consciousness.

At the Tuileries Palace, where she was taken for emergency care, it was found she had been pricked with a sharp instrument that penetrated four to five inches into her flesh. Three days later, at the Palais-Royal, a woman walking arm-in-arm with her husband was wounded above the hip by a stab from a stylus, and the unknown assailant fled.

On December 3, 1818, the Police Prefecture issued a press release:

“An individual, who has not yet been apprehended, is causing a particular kind of harm by pricking women from behind, either with a punch, a stylus, or the tip of an umbrella. Several cases, involving women aged fifteen to twenty, have recently occurred in the streets.”

Incidents multiplied, and the press reported on them. Newspapers like LʼIndépendant, Le Fanal, Les Débats, and Le Constitutionnel all discussed this new crime. Women, frightened, no longer dared to go out alone.

To catch the perpetrators, the police used decoys: young women, braving the “piqueurs,” walked the streets, followed by plainclothes officers. A reward of five francs was offered per day for each decoy.

They were told to look honest and keep their eyes down. About twenty women were ordered to report every morning at 9 a.m. to a wine merchant at the Montesquieu crossroads, where peace officers directed their patrols. Three officers followed them for eight days, with no result. Newspapers mocked this surveillance, saying the real aim was unclear, though eighty francs had been spent.

Finally, on February 1, 1820, the correctional police court sentenced a repeat offender, AugusteMarie Bizeul, a tailor, to five years in prison and a fine of five hundred francs for pricking four young women.

This did not stop the mania.

In 1821, the attacks continued.

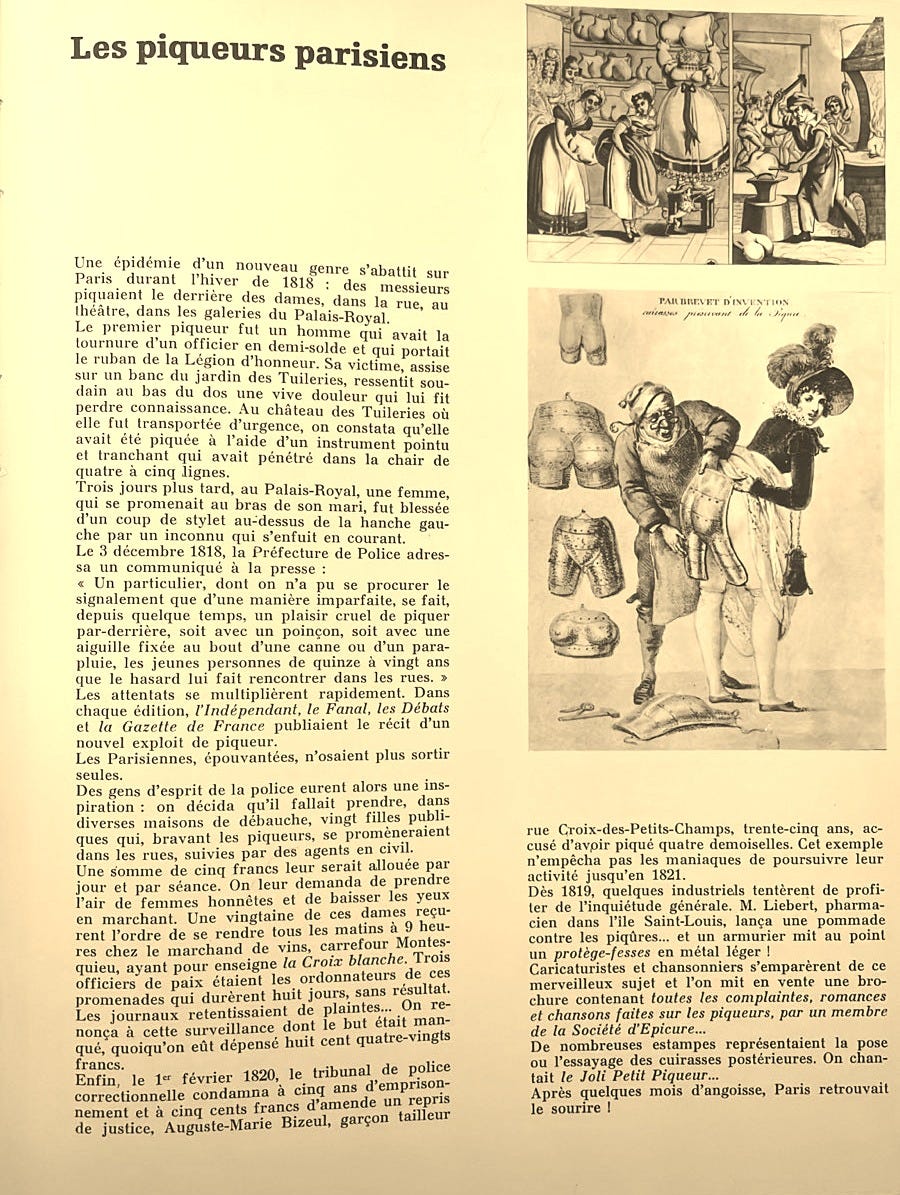

Some industries tried to profit from the general anxiety: a pharmacist created an ointment against “piqueurs,” and an armorer invented a metal “butt protector.”

Songwriters made fun of the situation, and caricatures abounded. After a few months of anxiety, Paris finally smiled again.

I read about a similar, if not almost identical, attack in Paris just yesterday. Can you draw some parallels between what happened yesterday with syringe attacks and this article from the 1800s?

Perhaps making a parallel between what might be happening in French political or socio-economic terms today.

-Pulp Conversationalist

Yesterday’s incident:

Both incidents share disturbing similarities in their execution and impact. In 1818, men targeted women in public spaces like the Tuileries gardens and Palais-Royal. Similarly, the 2025 attacks saw 145 people, predominantly women, pricked with syringes during a public festival, with at least 12 young women aged 14 - 20 hospitalized.

Both incidents occurred during periods of significant social tension in France. The 1818 attacks happened during the post-Napoleonic restoration period, a time of political and social uncertainty. The 2025 attacks coincide with France's current deep social divisions, including unprecedented political instability following the 2024 elections that resulted in a hung parliament